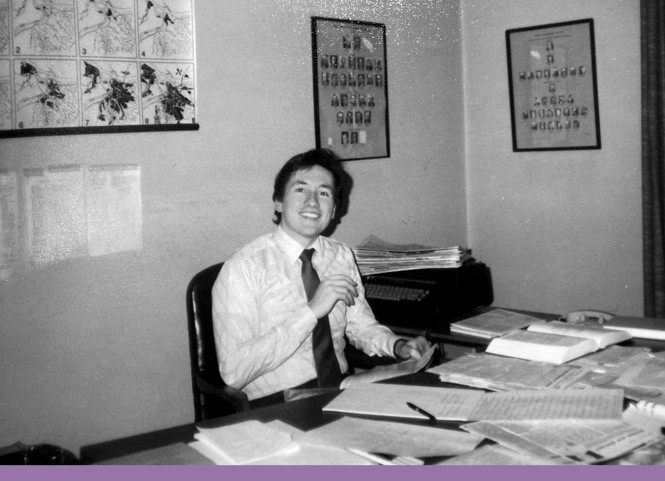

In the summer of 1984, after he finished his first U.S. Foreign Service assignment, in Yugoslavia, Jan Krc flew to Washington, D.C., for what he thought would be a couple of weeks’ training en route to his next post, in South Africa. He thought nothing of it when he was called in for a security debriefing early one morning at the U.S. Information Agency headquarters. There, in a nondescript conference room, he was met by two middle-aged men in suits. The session began with half an hour of preliminaries, but then swerved sharply.

Have you engaged in homosexual relations since age 18?

Oh, shit, he thought. Krc, who was 27, hesitated. He said he should get a lawyer. The questioners told him representation wasn’t needed; if he answered truthfully, he would soon be on his way to Cape Town. Believing them, he disclosed having had flings with two foreign nationals (not a violation of fraternization rules, as neither was from a hostile country). The interrogators drilled for details. They wanted the names of other Americans at the embassy who might be homosexual. Also any visitors he had had from the United States. When so-and-so visited, did you have sex with him?

The session continued for nine hours, with one short break when, sweating and fearful, Krc ran downstairs for food. The interrogators eventually demanded a written statement acknowledging his homosexuality. “In the end, I did sign what basically was a confession,” he told me. He left knowing that his career was in jeopardy, yet believing that he and the government were on the same side. “I still thought I was going to Cape Town, even after the end of the interview. Even as bad as it was, I thought, I was honest, so why shouldn’t I be going to South Africa?”

For Krc, a career in the Foreign Service had been a dream since adolescence. “I was one of those people who always knew what I wanted to do,” he told me, “and I had no plan B.” Born in 1956, he had grown up in Czechoslovakia under communism. His maternal grandfather did five years of hard labor in a uranium mine, ostensibly for listening to Voice of America broadcasts. His father refused to join the party and paid with a stalled career. The family’s requests to emigrate led only to harassment; they lost their apartment and had to live in a two-room flat with Krc’s grandmother. Desperate, Krc’s father took Jan and his brother and made a dash for asylum. Krc still recalls spending a night at a train station and hitchhiking to the Austrian border. Taking the oath of American citizenship as a teenager ranks among the proudest moments of his life.

“This country was really good to us,” he told me. “I wanted to give back.” But his interrogators had lied. “They knew that I wasn’t going anywhere.” Krc’s posting was revoked. He was transferred to a dead-end desk job in hopes, he assumed, that he would quit, and yet the government also refused to provide references to prospective employers. Krc would sit at that desk for nine years. “People knew I was damaged goods,” he said.

When he called his parents soon after his interrogation, they marveled at how clear the international connection sounded. He told them he wasn’t in Cape Town; there had been a delay. When he later decided to fight his dismissal, he knew he would have to out himself. His parents were conservative, and the conversation didn’t go well: His mother stayed in bed for days, and his father thought Krc would die of AIDS. They prevailed on him to see a hypnotist to try to change his orientation.

Krc lost substantial weight, along with his sex drive. He couldn’t sleep. “There was nothing I could do to get my mind off of it.” In some ways, the hardest thing was his disillusionment with the government he had trusted and pledged to serve. Its treatment of him was an unsettling reminder of the regime he had fled. “I was under the impression that things had changed,” he said. “I didn’t believe for the longest time that this could be happening. It struck me as so totalitarian. That’s definitely a thought that occurred to me: This should not be happening in the U.S.”

Krc was not the only one to have had that thought. Nearly three decades earlier, on a hot day in April 1958, when Krc was just a toddler, a 24-year-old U.S. Commerce Department employee named Madeleine Tress was summoned to a stifling room where she was startled to encounter two civil-service investigators. “The commission has information that you are an admitted homosexual,” one said. He asked what comment she wished to make. Under oath, without an attorney, she refused to answer, but they continued with detailed, rapid-fire questions. Had she ever been to the Redskins Lounge? Did she know Kate so-and-so? “How do you like having sex with women?” one investigator demanded. “You’ve never had it good until you’ve had it from a man,” he sneered. “Under intense questioning,” the historian David K. Johnson writes in his 2004 book, The Lavender Scare, from which this account is drawn, “Tress eventually admitted to some homosexual activity in her youth, but claimed she had ‘broken away’ from that since coming to Washington.” Though she refused to sign a statement prepared by the investigators, she understood that she had no choice but to resign from her job. “The interrogation,” Johnson reports, “was the most demeaning experience of her life.”

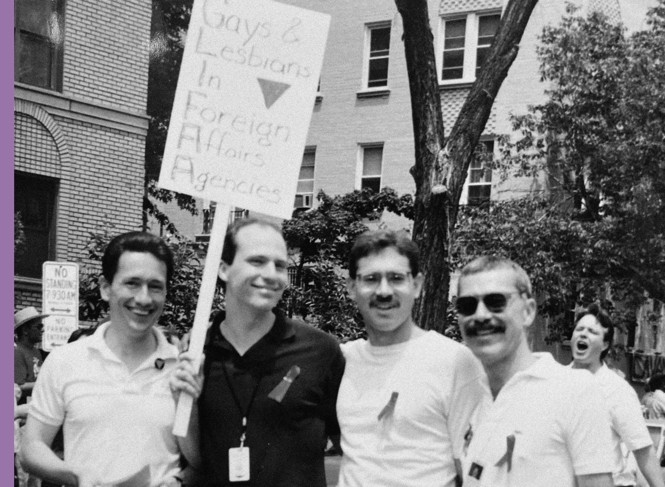

Incidents like these transpired by the thousands; Tress’s was not the first and Krc’s not the last. Tress died in 2009, a year before Congress rescinded its ban on gay and lesbian military service, the last remaining federal prohibition on the employment of gay people; she had spent half her life with a partner she loved but could not marry. Krc is still alive, but the government has not apologized for the abuse it inflicted on him, or for his time of panic and depression, or for the jobs and foreign postings he didn’t get, or for his ruptured personal and family life.

Well, perhaps that is not precisely true. On January 9, 2017, on the State Department’s website, Secretary of State John Kerry did post an official apology for the department’s relentless, decades-long persecution of homosexuals. By January 23, the page was gone, removed in one of the first acts of the incoming Trump administration. The government was sorry for two weeks.

[From the January/February 2024 issue: Spencer Kornhaber on Trump’s plan to police gender]

You may be aware that for decades the U.S. government fired homosexuals, the military discharged them, and police arrested them. Some of these actions are well within the living memory of most adults. Yet if you are like most people—including me, when I began researching this article—you have not fully appreciated that these policies were not discrimination of any ordinary sort. Beginning in the 1940s and continuing for more than six decades, the United States waged a campaign of legal, social, and psychological obliteration against its homosexual population. (Because society targeted what it identified as “homosexuality,” I will primarily use that term throughout this essay, but make no mistake: People who today would identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or gender-nonconforming were all targeted.) The campaign was initiated by the federal government but recruited all of society. The pressure could be felt everywhere. It found you not only at work, where you could be fired, or in bars and clubs, where you could be arrested, but also on the street and in public spaces, where you could be harassed or assaulted; in a doctor’s care, where you might be deemed mentally ill; at home, where you saw gay people ridiculed and pathologized on TV.

The goal, as the historian and legal scholar William N. Eskridge Jr. writes in his 1999 book Gaylaw, was not merely to disadvantage homosexual people; it was to erase homosexuality from every corner of public life. A 1964 report by the Florida state government approvingly quoted a scholar who said that “society would feel better if there were no homosexuals,” and that was exactly what society sought. Some of what America did to its LGBTQ citizens would have been right at home in places such as prewar Germany, Communist East Germany, and any number of repressive states today. Eskridge shows that, on paper, the anti-homosexual laws, regulations, and police practices in the U.S. at the height of its war on homosexuals were “virtually identical” to the anti-homosexual rules of Germany in the 1930s. The campaign stands, at its peak, as America’s purest national experiment with totalitarianism. Although not the cruelest or deadliest of America’s historical oppressions—no populations were decimated or relocated; no people were enslaved—it stands apart in its use of every governmental and social channel to eliminate the very thought of “deviance.”

And yet, for a long time now, the United States has failed to confront its past. The names and stories and lessons have been buried and are steadily being lost. As a society, we have never counted the victims, acknowledged their suffering, or compensated them even symbolically—though some of them, such as Jan Krc, are walking the streets among us right now.

In that respect, the campaign to erase homosexuality succeeded. And it continues today, as conservative activists crisscross the country seeking to wipe homosexuality and transgenderism from school libraries, from history classes, and from other curricula. Even as it is being forgotten, the campaign is being repeated.

In hindsight, America’s 20th-century obsession with homosexuality seems a bit baffling. Anti-homosexual persecution was not always prominent in American life. Laws against sodomy dated back to the early days of the republic, but “sodomy laws were understood, in the nineteenth century, primarily as instruments to regulate sexual assault,” Eskridge writes in his 2008 book, Dishonorable Passions: Sodomy Laws in America, 1861–2003. “Not a single reported sodomy case that the framers would have known about involved conduct in the home or consensual activities,” he notes. “In practice, police rarely enforced sodomy laws against anyone before 1880.” That began to change as the concept of homosexuality emerged in psychology and as gay subcultures emerged in cities. States and localities responded by enacting new sodomy laws and repurposing statutes criminalizing public indecency and vagrancy; in the first two decades of the 20th century, Eskridge writes, sodomy arrests in 12 big cities increased almost tenfold. Still, the numbers overall remained low.

World War II brought a sea change. Mobilization gathered together large concentrations of young men and created more opportunities for homosexuals to find one another, hang out, drink, dance, and have sex while the country was focused on the war effort. But as homosexuality and gender nonconformity became more visible, society reacted fearfully. The war’s end prompted a new focus on domestic affairs, and on the reimposition of cultural patterns—the nuclear family, traditional gender roles at work and at home—that mobilization had disrupted. The onset of the Cold War, meanwhile, raised a new existential fear, this time of subversion from within. In the public mind, communism and homosexuality intermingled as a shadowy threat to the American way of life.

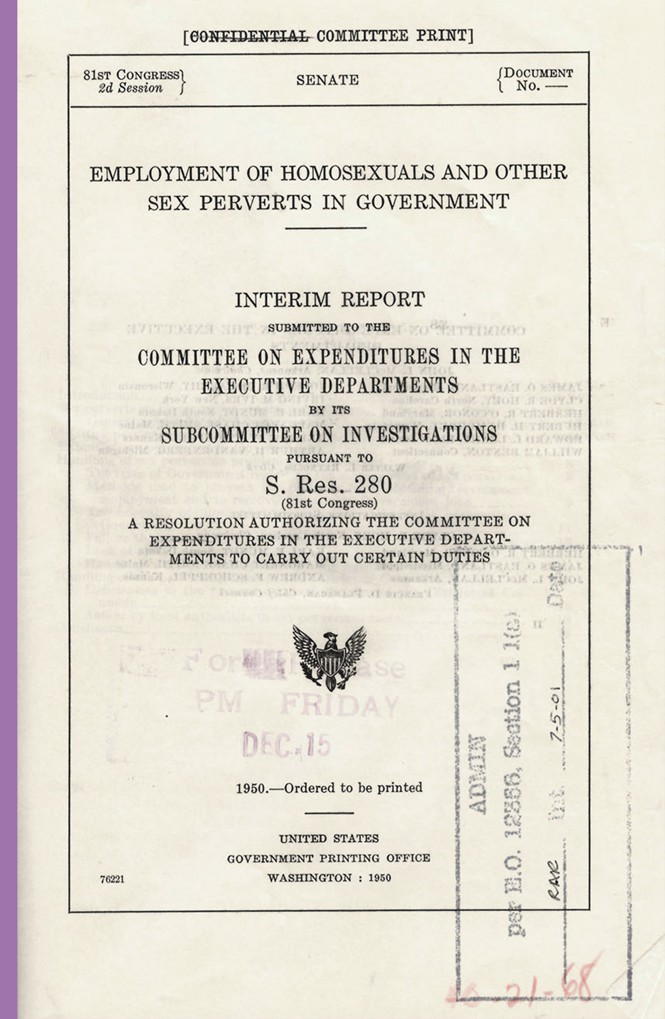

We usually think of a totalitarian order as centrally planned and imposed, but a decentralized system of mutually reinforcing repressions can have much the same effect. In the 1940s, the country began locking the elements into place—starting with what amounted to a declaration of war by the federal government. In 1945, the U.S. Civil Service Commission announced that it regarded homosexuality as “notoriously disgraceful” and homosexuals as unsuitable for federal employment. That same year, the firing of homosexuals became unofficial State Department policy; the U.S. Park Police in Washington, D.C., initiated a “pervert elimination campaign”; and the FBI director, J. Edgar Hoover, decried homosexuals as “depraved human beings, more savage than beasts, [who] are permitted to rove America almost at will.” In 1950, a Senate committee found homosexuals to be emotionally unstable and of weak moral fiber, urging vigilance against their presence in the halls of power. In 1952, Congress barred “persons afflicted with psychopathic personality”—by which it meant homosexuals—from entering the country.

Then, in 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower issued his infamous Executive Order 10450, one of America’s most grotesque civil-rights violations, declaring “sexual perversion” to be a security threat. The effect was to authorize all federal departments and agencies to root out and terminate sexual deviants. Although the order also named such conditions as mental illness and addiction as security risks, only homosexuals were fired automatically, without excuse or exception.

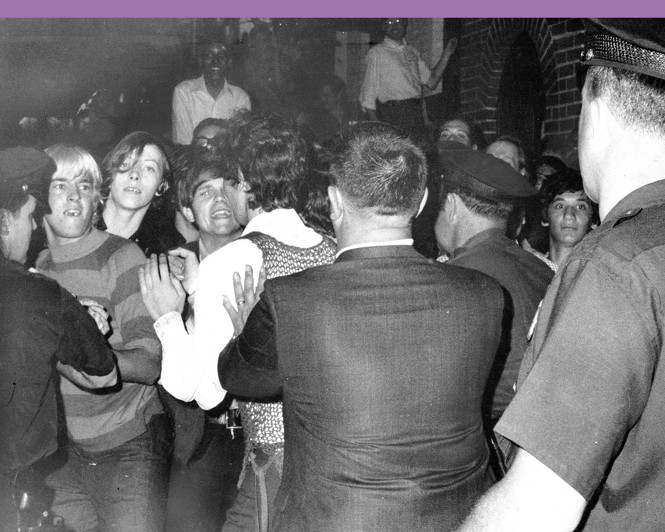

The federal government’s mid-century mobilization against homosexuals is the best-remembered part of the war on homosexuality, but it was only the beginning of that war. It catalyzed the creation of an even larger front of repression. The “Lavender Scare” signaled that homosexuality was not merely distasteful, but dangerous—a mortal as well as moral threat. States and localities, previously sporadic in their enforcement of anti-homosexual measures, responded by going all-in: surveilling, entrapping, arresting, harassing, exposing, and prosecuting homosexuals at previously unknown rates. In 1950, Philadelphia alone hauled 200 homosexuals a month into court, according to Eskridge. Over the next two decades, police raids on bars and private gatherings rose quickly across the country. Police in the District of Columbia typically made more than 1,000 arrests each year. Some were tried and convicted, but many were booked and released after an interrogation, a fine, and—most consequentially—the creation of an arrest record or news report that branded them as deviant and followed them for life. The goal was not so much to score convictions as to instill terror.

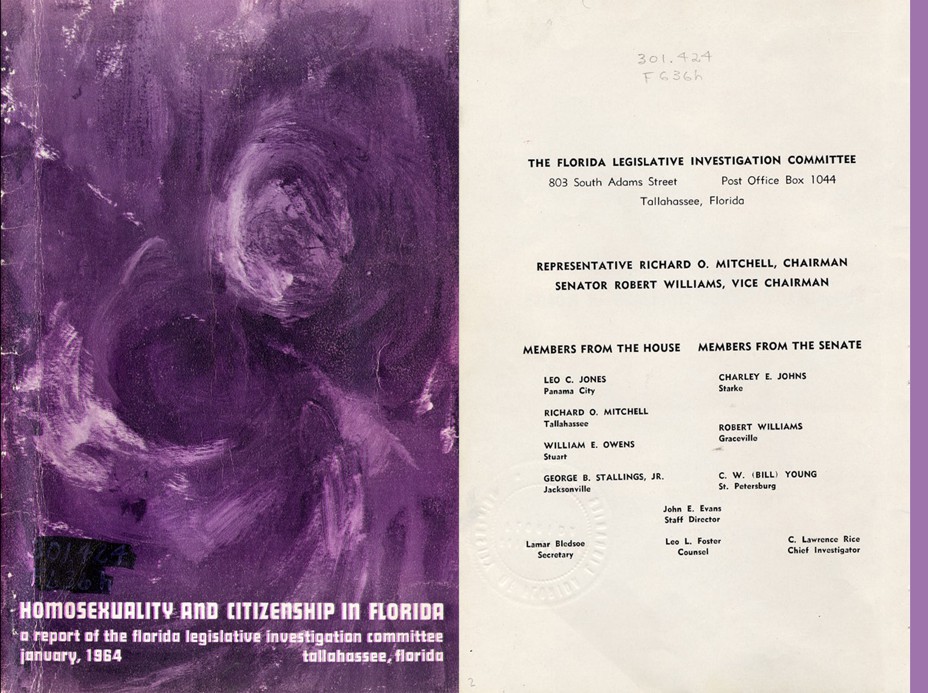

Exemplifying the Stasi-like nature of the regime, and how the local, state, and federal machines all worked together, was Florida’s “Johns Committee,” as the Florida Legislative Investigation Committee was informally known. Established in 1956 to harass the NAACP, it soon pivoted to homosexual teachers and state employees. By compiling lists of suspected homosexuals and surveilling such places as bars, libraries, and wooded areas, as the historian Stacy Braukman writes in Communists and Perverts Under the Palms, it gathered names by the hundreds. Its interrogations borrowed directly from Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-communist playbook, demanding, “Are you now or have you ever been involved in any type of homosexual activity?” Examinees were humiliated at length, asked, for instance, “whether or not you received the most pleasure out of giving a blow job or receiving one.” If you name names, the subjects were told, you might be spared arrest and public exposure. And so professors turned in students, who turned in classmates and other professors. Terrified victims resigned from their job on the spot. With bureaucratic pride, the commission tallied wrecked lives. Teachers’ certificates revoked: 71. Professors removed from universities: 14. Public-school teachers with information in the committee’s files: 105. And, notably, Federal employees fired: 37. The Johns Committee could not fire federal employees, but it could and did report its findings to the federal authorities, who were glad to act on the information.

By the mid-1950s, according to the historian Allan Bérubé in his 1990 book, Coming Out Under Fire, state and local governments across the country had copied the federal government’s ban on the employment of homosexuals, extending it to more than 12 million workers (or more than 20 percent of the workforce). Many private employers followed suit. Although some people were denied jobs or lost them, the broader effect was to drive homosexuals deep into the closet. In The Lavender Scare, Johnson quotes a clerk-typist at the Veterans Administration who refused promotions: “I know that my fear, my terror at the time, was that if I became anything other than a clerk-typist, then I might get found out, and then I would lose my job,” he said. “I had the ambition, but I was frightened.”

After a firing and exposure, one way out was suicide—but erasure could continue even in death. When one State Department employee killed himself after two days of interrogation, the department told his parents, according to Johnson, “that he was despondent because of bad health, making no mention of the repeated interrogations or homosexual admissions.” At the time, this was considered compassionate.

By 1960, same-sex relations were illegal in all 50 states. Homosexuals, however, did not need to have sex to be arrested; vague laws against solicitation, indecency, lewdness, loitering, and obscenity effectively criminalized the mere act of flirting, socializing, or hanging out. “They could always find something,” Dale Carpenter, a legal scholar and historian, told me. “It was hazardous to be gay. You were part of a class of people defined by criminality. If you were gay and you were in public, you were liable to be harassed and arrested for some trumped-up reason.”

And in fact, just as you didn’t need to have sex to be arrested, you also didn’t need to be doing anything publicly. By 1960, 21 states had “removed public-place requirements from their lewdness and indecency statutes,” Eskridge writes. “In most of the United States it became a crime not only for same-sex couples to engage in private consensual sodomy but even to propose such conduct at any time or place.”

At any time or place. Homosexuals were at risk anywhere they dared to express themselves. In 1955, Baltimore recorded 162 arrests for disorderly conduct in a bar after police observed hugging and kissing; in 1960, at a club in San Francisco, 103 were arrested for same-sex dancing. “They were easy arrests,” an officer who led the 1969 raid at New York City’s Stonewall Inn said years later; until the famous riots that year, homosexuals usually went quietly, terrified of exposure and hoping for leniency. My cousin Michael Brittenback recalls leaving the Déjà Vu bar in Indianapolis one night in 1969 or 1970, too tired to stay late and hook up. The next morning, he saw in the paper that the bar had been raided and several dozen arrested not long after he left. “They listed the names,” he told me. “Many of them lost their jobs.” Around the same time, the police confronted him in a park sweep (he was told to leave but was not arrested, because he was alone). “There was no safe place,” he said. “It felt like a police state.” Even after Stonewall, social gatherings were raided well into the 1970s. If you made a living in a “respectable” profession, hanging out with friends at a gay bar even once could be a career-ending decision.

Official acts of persecution, executed loudly over many years, could not fail to echo in the culture at large; and indeed, they created a permission structure for blatant prejudice. Mass media amplified the message that homosexuality was disgusting and terrifying. In a 1966 article, Time magazine—taking what was then regarded as a humane tack—called homosexuality “a pathetic little second-rate substitute for reality, a pitiable flight from life. As such it deserves fairness, compassion, understanding and, when possible, treatment. But it deserves … no pretense that it is anything but a pernicious sickness.”

Providing both legitimacy and impetus for the eradication of homosexuality was psychiatry, the most soul-crushing cog in the repressive machine. Psychiatry of the era defined homosexuality as a mental disorder. And as the historian George Chauncey has noted, more than half the states empowered police and courts to force those convicted—or in some cases, merely suspected—of being “sexual deviants” to undergo psychiatric exams. Some were committed involuntarily. In places such as Saint Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C., homosexuals were “treated” with methods that could include injections of hormones, electric shock, lobotomization, and the use of “insulin shock therapy” to induce a purportedly therapeutic coma. The latter treatment, regarded at the time as a kind of injectable lobotomy, was administered to Thomas H. Tattersall, who was admitted to Saint Elizabeths in the mid-1950s after being forced out of a Commerce Department job. “Agents serially interrogated Tattersall while he was ‘in a kind of zombie state’” at the facility, according to a 2018 report by the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C., a nonprofit dedicated to recovering LGBTQ history. “During one interrogation, Tattersall identified gay employees across more than twenty federal agencies.”

In 1973, the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its list of mental illnesses, but the damage lingered for decades. That same year, Farrall Instrument Co. of Grand Island, Nebraska, proudly advertised a line of devices for home-psychiatric treatment of male homosexuality. The “Visually Keyed Shocker” showed alternating slides depicting conventionally attractive women and men (“stimulus scenes”). The latter were accompanied by an electric shock. If you were a latent homosexual and desperate for a “cure,” you could buy one for $600 or more.

This was the world I grew up in (I was 13 in 1973). Everything I saw and heard conveyed that something was wrong with me, and that I must keep it secret, especially from the people I loved and depended on. So warped was my inner world that, until I was 25, I could not bear to face the blatant truth about myself and managed to believe that I was asexual, some kind of freak who could never love anyone (a story I told in my 2013 book, Denial: My 25 Years Without a Soul). In that respect, though I never owned a “Visually Keyed Shocker,” I administered a full course of self-erasure in the privacy of my mind.

The entire system of erasure was backed by violence. In 1986, the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force testified to Congress that of 2,000-plus gay and lesbian people surveyed, more than one in five men and nearly one in 10 women had been physically assaulted because of their sexual orientation; more than 40 percent had been threatened. Except in a few spots in a few cities, homosexuals dared not hold hands for fear of a beating. I recall, in the 1980s, hiding my purchases when I left the local gay bookstore in Washington, D.C., worried that the pink plastic bag would attract dangerous attention. I could not be confident that the police, if called, could or would help.

The arrests, the raids, the firings, the networks of informants, the coercive investigations, the surveillance, the obliteration of privacy, the abuse of medicine, the drumbeat of street violence, the disruptions of social gatherings and family life—each element of the regime supported and amplified the others. Only by standing back and seeing the regime whole does one appreciate how all of society was bent toward repressing every aspect of homosexual life, wherever it might appear. The goal was to suppress not just deviant activity but deviant expression and even deviant thought. That was what made it literally totalitarian.

The point was not lost on homosexuals at the time. In a 1961 Supreme Court appeal (which the Court declined to hear), Frank Kameny made the argument explicitly. Kameny, a Harvard-trained astronomer, was fired by the U.S. Army Map Service for homosexuality in 1957 and went on to become the 20th century’s most important LGBTQ civil-rights leader. By firing him for no other reason than his sexual orientation, Kameny claimed, the government had engaged in employment discrimination. More than that, however, it had violated the Constitution “by establishing a tyranny over the mind of its citizen.”

In The Lavender Scare, Johnson quotes Madeleine Tress: “You lived not knowing what would happen next … You would be socializing with somebody, and then they disappeared, they had gotten kicked out and left town … I can’t describe that kind of fear.” A gay man, likewise: “You would go to work and you would ask, ‘Where is lieutenant so-and-so?’ They wouldn’t answer. They had discovered that he was gay, and he was separated. His desk was cleaned out. You never saw the man again.” American homosexuals were not murdered or sent to Gulags, yet they were nonetheless made to vanish, suddenly and without explanation, year after year. Compounding that injustice is another: Today, the victims remain unseen. Who were they? How many were there? What were their stories? The quite extraordinary answer is that we do not know and have not asked.

The federal government has never accounted for its homosexual removals. The historian James Kirchick, the author of Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington, estimates the total to be between 5,000 and 10,000, but even that wide range is something of a guess. Perhaps 1,000 were dismissed by the State Department, with emphasis on perhaps. When I asked Eskridge, the leading authority on the topic, how many homosexuals were arrested by local police and other law enforcement, he said, “Hundreds of thousands.” Beyond that very loose generality, we do not know the dimensions of the dragnet, partly because centralized records were not kept. Of firings and coerced resignations in the private sector, psychiatric abuses, blackmail, and suicides, we have even less documentation.

Victims’ names and stories, such as Thomas Tattersall’s, surface sporadically in documents and government records, but Charles Francis, who leads the Mattachine Society, says that obtaining government records has been difficult, slow, and expensive, often requiring Freedom of Information Act requests and sometimes lawsuits to enforce them. The Mattachine Society encourages victims and their descendants to search attics and drawers for documents and mementos of the war on homosexuality, which university and private archives are beginning to collect and collate. Kameny’s own papers—precious artifacts of civil-rights history—are ensconced in the Library of Congress. But those actions, although important, are fragmented and ad hoc, nothing like the creation of a national record. “It’s been erased,” Francis says of the past. “It’s been destroyed; it’s been sealed. It’s not taught. The new generation knows nothing about it.”

Hardly anyone, whether LGBTQ or straight, knows, for instance, that in 1954 a respected Democratic U.S. senator, Lester Hunt of Wyoming, blew his brains out with a .22-caliber Winchester rifle in his Senate office because Republican senators were blackmailing him over his gay son, a crime for which they faced no consequences. If even so shocking an event could be wiped from memory, it is no wonder that so much of the past has been effaced. According to a 2021 report by the Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network, only about one in seven American students receives any instruction that includes positive representations of LGBTQ people or topics. Yet conservative activists are rushing to further reduce instruction involving gender identity and sexual orientation. According to the Movement Advancement Project, seven states ban instruction about LGBTQ people or issues in public elementary or middle schools. Florida and Kentucky extend their ban through high school.

Last spring, it was reported that investigators from the Florida Department of Education, operating under the state’s law prohibiting teaching about gender identity or sexual orientation, had summoned fifth graders out of class to question them about a teacher’s screening of a PG-rated Disney movie that portrays an openly gay character. The school soon announced, “While not the main plot of the movie, parts of the story involves [sic] a male character having and expressing feelings for another male character. In the future, this movie will not be shown.”

The Johns Committee, whose investigations ended within living memory, would be proud.

Shunted to a bureaucratic office job, Jan Krc decided to fight to get his career back. He had heard of an activist who helped people in his situation—none other than Frank Kameny. Through Kameny, he secured legal representation and began a slog of hearings and litigation. At his first hearing, in 1985, the government lawyer’s opening words made the issue plain: “Mr. Krc is an open and notorious homosexual.” The case dragged on for a decade. Eventually, in federal court, Krc lost. Nonetheless, in 1993, after the Clinton administration came in and attitudes had relaxed, he was allowed to reapply to the Foreign Service and was admitted anew. He served until 2018, when he retired.

Krc, in his 60s and living in Washington, is not an old man. What happened to him is not ancient history. He finally beat his persecutors, but only after his career was upended, his family disrupted, and his whole life colored by a degrading battle against the government he wanted to serve.

In the past several Congresses, Democrats have introduced the Lavender Offense Victim Exoneration (LOVE) Act, which would apologize for the State Department’s Lavender Scare persecutions and offer formal vindication to victims like Krc. It has gone nowhere. Likewise, a Senate resolution first introduced in 2021 by Tim Kaine of Virginia, with Tammy Baldwin of Wisconsin and various other Democratic co-sponsors, would apologize on Congress’s behalf to all LGBTQ victims of federal persecution. Official apologies are nothing new; Congress has apologized to victims of slavery and lynching, to Japanese Americans, to native Hawaiians, to Native Americans, and to Chinese immigrants. Gay and lesbian people have received a few apologetic gestures: In 2009, the government apologized to Frank Kameny, 51 years after his firing. In April, President Joe Biden issued a proclamation acknowledging the “injustice” of the Lavender Scare (but not apologizing for it). But those gestures are sporadic and mostly unknown to the public. Nothing has come close to national recognition.

When I asked Kaine why it’s important for the government to apologize for its war on homosexuals, he replied, “I don’t think you just cast aside those who suffered under a previous repressive structure. They just wanted to serve their country, for God’s sake. And so many served at the highest levels of quality and courage. We’ve got to have some reckoning about that.” Kaine’s resolution enumerates and condemns the federal government’s depredations, from the formal military ban in 1949 until 2014, when President Barack Obama signed an executive order protecting LGBTQ personnel from discrimination by federal agencies and contractors. “The Senate as an institution was complicit in this,” Kaine said. “This is not only an expression of regret for the thousands of people who had their careers thwarted; it’s an expression of responsibility.”

Abroad, foreign governments in countries including Australia, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, and the United Kingdom have issued apologies for their past abuses of homosexuals. Some have provided compensation to victims; others have retroactively vacated unjust convictions. The United States has done none of those things. In fact, as of 2023, sodomy laws, though now unconstitutional, remained on the books in 12 states, a defiant thumb in the eye of LGBTQ people.

This is inadequate. Great nations own up to their past and pay their debts to their violated citizens. Kaine’s resolution, if passed, would be an important step toward doing that. But it would be the barest of starts. Congress should also establish a truth commission: a body tasked with assembling and memorializing the full story of what the government and society did to homosexual Americans. A National Center for LGBTQ History, chartered by Congress with public and private funding, could serve as a repository for records, mementos, and stories of those who suffered, with a mission of ensuring that the past and its victims are not forgotten.

States that outlawed gay sex and harassed homosexuals (which is to say, all of them) should apologize, and states with sodomy laws should repeal them. Governors should retroactively pardon those convicted of sodomy, solicitation, or other offenses that criminalized homosexuality. State boards of education should make sure that the LGBTQ civil-rights struggle is included in history and civics standards.

And Congress should pay restitution to living victims of government arrest, firing, or military discharge. The symbolism matters more than the amount; the point is to recognize in a tangible way, not merely with words, the victims’ lost livelihoods and reputations. Jan Krc deserves that much.

A proper accounting of America’s long war on homosexuals is not, as some might have it, pandering to modern grievance culture; it would elevate America’s ideals. As far back as 1957, the state of Massachusetts officially repudiated the verdicts of the Salem witch trials. No one today regards the country as weaker or more divided because Congress repudiated the internment of Japanese Americans, or because the Senate apologized for its refusal to adopt anti-lynching laws. By acknowledging our failures, we affirm our principles, making our country stronger.

Nor would such an accounting draw attention away from LGBTQ groups (such as trans people and LGBTQ people of color) who face the heaviest discrimination today. The war on homosexuals affected everyone we today identify as LGBTQ. It also affected people of all races and classes. It violated the rights of all Americans. Nonwhite people, women, and trans people were all targeted. All deserve to be remembered.

Although the bar raids, park sweeps, mass firings, sodomy arrests, and shock treatments are thankfully in the past, that neither entitles us to forget those wrongs nor makes it wise to forget. The American Civil Liberties Union, which tracks state legislation, lists more than 500 anti-LGBTQ bills introduced during 2023, a nearly threefold increase over the number in 2022. Meanwhile, eliminationist rhetoric targets LGBTQ people: In March, the conservative commentator Michael Knowles said that “transgenderism must be eradicated from public life entirely,” exactly what was said about homosexuality two generations ago; in June, Donald Trump said of transgender athletes, “These people are sick; they are deranged,” an echo that is unmissable if you remember the past. We must not fail to recognize where such threats have led, and still lead.