What are friends for?

For knocking around with, cracking a joke, sharing a doobie, firing a paintball? Or for guarding in the angelic citadels of their being the essential soul-image of you and everything you might eternally come to mean, while you in shining symmetry and perfect vulnerability do the same for them?

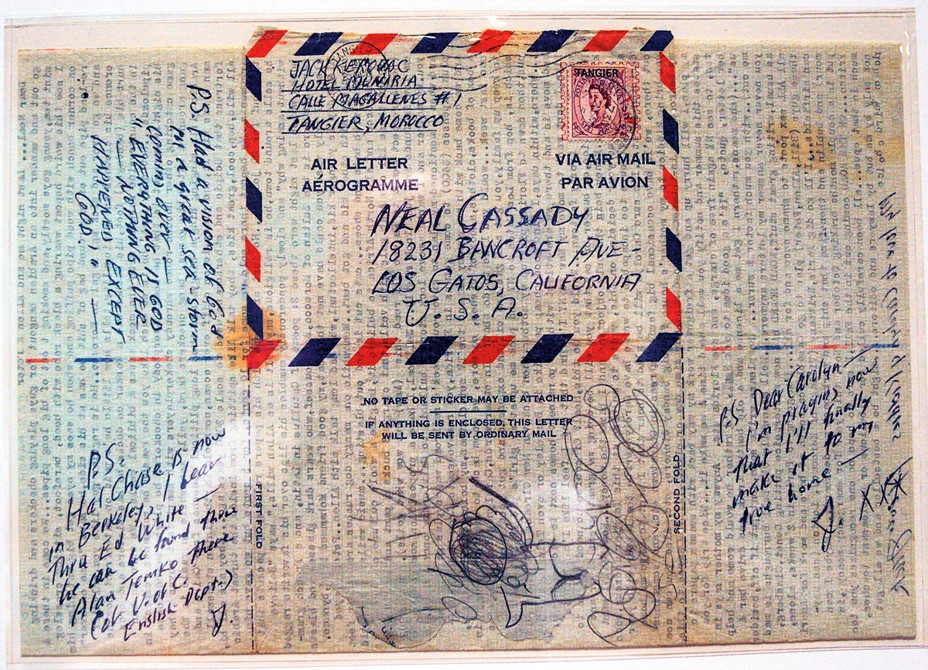

“The time has come for me to write a full confession of my life to you,” Jack Kerouac typed thunderously to Neal Cassady in December 1950, in the first of a sequence of massive, rumbling-and-rolling autobiographical letters, steeped in memory and mystery, that he would mail from Queens, New York, to San Francisco. “Bullshit is bullshit. Everything’s got to go this time. No one can take it but you. From the very start we were brothers.” Cassady at the time was supporting a young family by working as a brakeman on the Southern Pacific Railroad; Kerouac was in retreat, annoying his new wife, Joan; brooding over the poor sales of his big, Thomas Wolfean debut novel, The Town and the City; trying and failing to find a new voice/style/idiom/rhythm in which to project his own experience, and the flavor of his distinctly bruised consciousness, more immediately onto the page. Despite great efforts and grave auto-examinations, it wasn’t happening: false starts, loose ends, quarreling selves. His next book—working title: Gone on the Road—had been trapped in a state of unbecoming.

[From the November 1998 issue: In the Kerouac archive with Douglas Brinkley]

But now, suddenly, he was getting somewhere. The door was open. Earlier that month a nearly 16,000-word handwritten letter from Cassady, a jittering, picaresque fragment about his sexploits as a young hoodlum in Denver, had snapped Kerouac awake and unlocked him. Cassady’s prose, he wrote back instantly, “the muscular rush” of it, was untouchable, an American summit. “No Dreiser, no Wolfe has come too close to it; Melville was never truer.” And now, in (slightly) more measured response, feeling himself and his friend to be “contending technicians in what may well be a little American Renaissance of our own and perhaps a pioneer beginning,” he was ready to let go, to let it out, to be himself—which meant himself-as-a-writer—at last.

Is there anything we can learn, in this centennial year of Kerouac’s birth, from the energy that passed between these two men? Between Kerouac the college football player gone wrong, lugging his great dark literary sadness from coast to coast, and Cassady the car thief, pool-hall hustler, bus-station seducer, speed freak, wildly sensitized responder-to-jazz, devouring monologuist, and (according to acquaintances) psychopath?

On the Road would spectacularly revive or replant the idea of pilgrimage in the American imagination—pilgrimage as physical and spiritual exposure in motion, where the kingdom of heaven generously lowers itself, descends as a kind of glorious pressure and then (if you’re lucky) comes crashing through. The Kerouac-Cassady friendship, with its many way stations in the American night, was yet another kind of pilgrimage: two men, traveling into each other, guided or misguided by love, as far as they could go. Beyond sanity, it might be said—certainly beyond safety. Do we still do friendship like this in America? Can we?

Eros played a part, no doubt: Kerouac was a keen appreciator of Cassady’s physical beauty and prowess, “enormous dangle and all,” and the pair were frequently in triangular situations with women. At the same time, theirs was in the strictest definition a platonic relationship: Tricky characters that they both were, dudes leaving churned wakes of confusion behind them, each man treasured and maintained through all vicissitude an ideal of the other, spirit-Jack and spirit-Neal. “I’m completely your friend, your ‘lover,’ ” Kerouac wrote to Cassady in Visions of Cody, “he who loves you and digs your greatness completely—haunted in the mind by you.”

[From the December 2019 issue: James Parker on Hunter S. Thompson’s letters to his enemies]

Of course, the literary traffic was pretty one-way. While Cassady may have been a genius—or just a genie—of American experience, Kerouac was a genius of words. So Neal didn’t write (much) about Jack; Jack wrote about Neal. First as Dean Moriarty in On the Road, the breakthrough draft of which he banged out in a three-week inspiration binge in April 1951 (although it wouldn’t be published until 1957), and then—more wildly and blissfully—as Cody Pomeray in Visions of Cody. This was the book that Kerouac considered his “great one,” 400 pages written in “my finally-at-last-found style & hope.” “I wanted,” he wrote in a prefatory note, “a vertical metaphysical study of Cody’s character and its relationship to the general ‘America.’ ”

Dean Moriarty is a creature of jangles and manias—“Fury spat out of his eyes when he told of things he hated; great glows of joy replaced this when he suddenly got happy; every muscle twitched to live and go”—but he has an outline and a shape: He’s on the road, burning down the horizontal axis, a character. Cody Pomeray, by contrast, raised on (and by) the streets of Denver, is a soul. Kerouac’s account of him is all verticality: the God’s-eye view, or an attempt at it. As the son of a homeless alcoholic, “a Larimer street wino,” he is socially, morally, and perceptually out there, bareheaded to the heavens and at the mercy of the system (when he’s not running from it). On the street, in the reformatory, framed by huge American skies, he’s “a young guy with a bony face that looks like it’s been pressed against iron bars to get that dogged rocky look of suffering.”

So here it was, finally-at-last-found: the quintessence of Neal, expressed in the quintessence of Jack. A sprawling collage of reminiscences, imaginings, transcriptions of tape-recorded conversations, and prose on the point of becoming poetry, Visions of Cody doesn’t swing like On the Road; that heady patter is replaced by a deeper flow. Some of it is shockingly beautiful, an artistic consummation for Kerouac. Stray Catholics pray in St. Patrick’s Cathedral at dusk: “Now the window darkens to match the great transformations without, refracting them inward to these kneelers.” (Kerouac is painting like an old master here, in lovely, lugubrious oils.) Young Cody dodges police cars—“a flash of evil two-toned black and white with shiny antenna and the growl of the radio”—and contemplates the “lamby clouds of babyhood and eternity” over Colorado. And some of it (those transcripts, Jack and Neal high and babbling) is unreadable. “Crazy,” pronounced Allen Ginsberg, Kerouac’s other bosom buddy, to whom he sent a draft in 1952, “(not merely inspired crazy) but unrelatedly crazy … What are you trying to put down, man?”

[From the November 1966 issue: Allen Ginsberg’s “The Great Marijuana Hoax”]

Visions of Cody is definitely a trip. A showcase for Kerouac’s prodigious powers of recall (one can imagine him almost disabled by them at times, like Funes the Memorious in the Borges story), it is a sinking, saturating experience. The voice of the author, meanwhile—stripped of ambition, stripped of literature, stripped of everything but the desire to know and be known by Cody, and to confess this dual knowledge—is that of a kind of clown-saint, a battered pilgrim floating in American space: “Weep for me, weep for anybody, weep for the poor dumbfucks of this world.” And again: “I accept lostness. Everything belongs to me because I am poor.”

The Beats, say what you like about them, could do friendship. Split apart and self-affrighting as we currently are, it’s hard even to imagine the magnanimity of their commitment to one another. Ginsberg would come round to Visions of Cody in the end, calling it “a giant mantra of Appreciation & Adoration of an American man, one striving heroic soul.” Kerouac’s love for Neal Cassady gave him America—held-by-nothing, got-nothing America—as his subject, and gave him, too, the language in which to write about it. “How blissful the destitute, abject in spirit,” says Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount in David Bentley Hart’s translation, “for theirs is the Kingdom of the heavens.” And what if part of this destitution, this laid-openness, is true, naked friendship—the embrace, in all its genuine scale and glory, of another human soul?

This article appears in the April 2022 print edition with the headline “The Story of Jack and Neal.”