Illustrations by Miki Lowe

When the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam published his collection Tristia in 1922, the Bolshevik government had begun to tighten its grip on artists, pressuring them to use their talent for propaganda. Though he sympathized with the socialist cause, Mandelstam didn’t believe in writing for any political agenda. But he knew how grave the consequences of refusing could be: All around him, artists were fleeing or falling victim to the state. His fellow poet Nikolay Gumilev had just been executed, in 1921.

Tristia was a subtle rebuke to Bolshevik intimidation: Instead of glorifying the Soviet Union, Mandelstam mined ancient Greek mythology for themes of love, beauty, death, and eternal life. He seemed to be reaching for some transcendence from the chaos of his own country—and perhaps from his own mortality, of which he must have been so keenly aware. Mandelstam eventually experienced torture, exile, and imprisonment, and died in a transit camp at the age of 47.

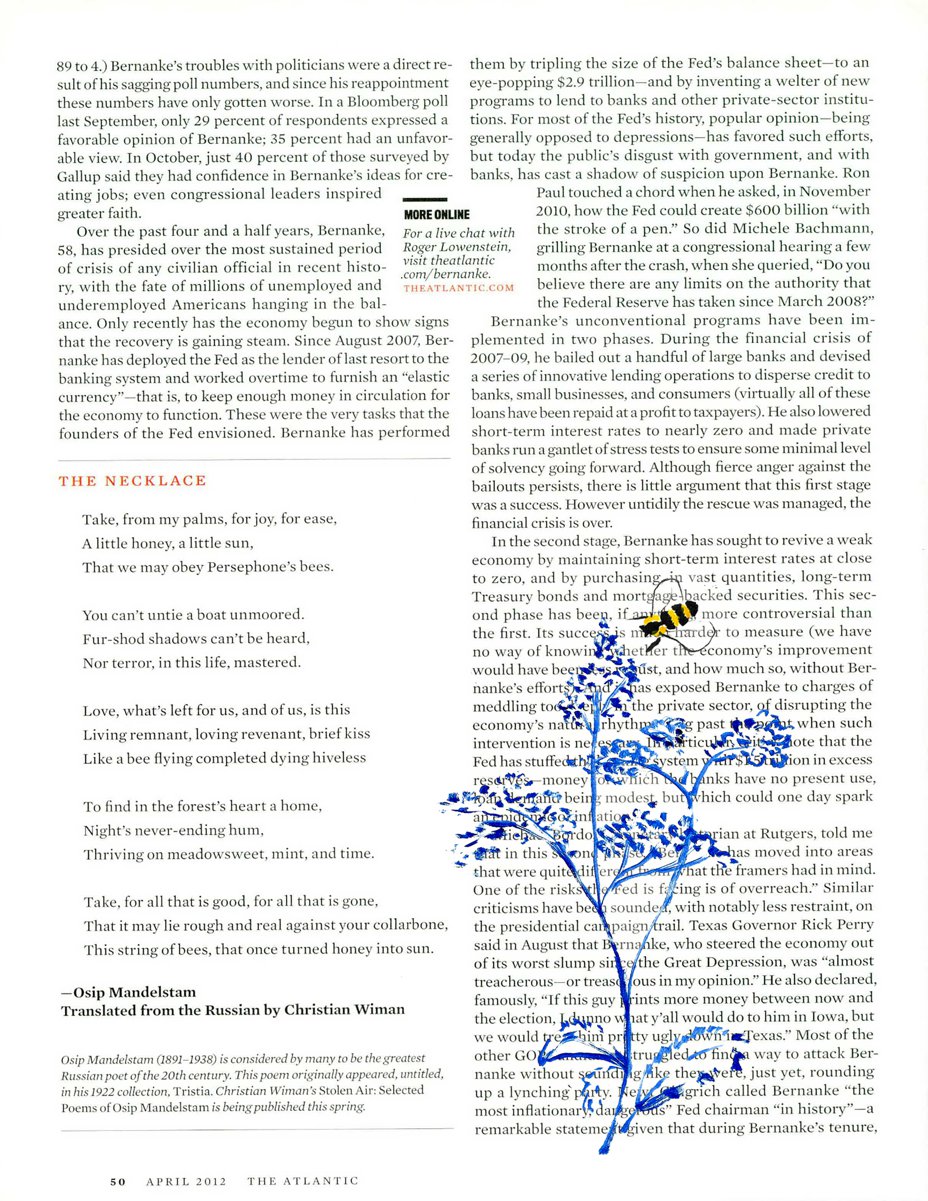

“The Necklace”—first published in Tristia and translated by Christian Wiman for The Atlantic in 2012—invokes Persephone, whose nickname was Melitodes, or the Honeyed One. Persephone is the queen of the underworld, but she’s also the goddess of spring; her presence brings life back after the dead winter on Earth, creating the seasons. Bees are a perfect symbol for such cycles. Some ancient Greeks believed them to be reincarnated human souls. And honeybees, whose life spans are fleeting, pollinate plants and produce honey before they die, allowing other creatures to thrive.

Here, Mandelstam imagines a necklace—a gift, like an offering to the gods—made of bees who perished turning honey into sun. “You can’t untie a boat unmoored,” he writes, “Fur-shod shadows can’t be heard, / Nor terror, in this life, mastered.” This poem is a call for mercy. It’s also an expression of the hope that, although darkness cannot be driven from humanity, some sweetness might come from it. Before death, he says, we must harvest what we can from love: “what’s left for us, and of us.”

You can zoom in on the page here.