Humans can move through time in only one way: forward, second by second, even when we set the clocks ahead an hour. But literature isn’t bound by the same rules. When narratives take place in the past or future, transporting the reader to the scene of events that already occurred or are expected to happen, that’s a kind of time travel exclusive to storytelling. For example, a Nomi Stone poem about cleaning mussels begins in the present, as the speaker prepares a meal. Then it vividly considers her wife’s childhood, even though the speaker wasn’t present then. It ends with a lament: “Isn’t it beautiful and terrible to exist inside / time: to already be not there but here then here—”

In poetry and in prose, time can warp, twist, and buckle. Authors conjure up the past in the present tense, or they make it relevant to contemporary life. Lauren Groff’s recent novel, Matrix, about a nun in the 12th century, draws heavily on her philosophy that “we are all embedded in the cyclical nature of time,” as she told Sophie Gilbert, and its concerns are surprisingly modern. In his short story “Person of Korea,” Paul Yoon uses fiction to examine the family history that he “will die knowing very little about,” as he says. And for years, Alejandro Zambra’s novels have tackled the fallout from the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile, but his newly translated Chilean Poet begins in the 1990s and meanders its way to the present, considering what the country’s future might hold.

Writing can also help us rethink how we measure time. The seven-day week, for example, isn’t a natural phenomenon, though it’s an extremely durable one, writes the historian David Henkin. And through books, we might ultimately consider how finite our lives are. That perspective shift is at the heart of Oliver Burkeman’s starkly named Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals. It’s a manual for mourning, but mostly accepting, what Stone writes about in her poem: how it’s both “beautiful and terrible” to be stuck moving ahead, one minute at a time.

Every Friday in the Books Briefing, we thread together Atlantic stories on books that share similar ideas. Know other book lovers who might like this guide? Forward them this email.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What We’re Reading

Millennium / Gallery Stock

“Thinking of My Wife as a Child by the Sea, While We Clean Mussels Together”

“I love this quiet house by the water / and lighting the fire and imagining my wife as a child / throwing a sweater over her pajamas to cycle with no hands / by the sea.”

📚 “Thinking of My Wife as a Child by the Sea, While We Clean Mussels Together,” by Nomi Stone

Illustration by Vanessa Saba; images by Leonardo Cendamo / Getty

The writer who saw all of this coming

“Matrix, a book set in the 12th century, is also a communion with now: our impulses, our foibles, our enduring discomfort with female power.”

📚 Arcadia, by Lauren Groff

📚 Fates and Furies, by Lauren Groff

📚 Florida, by Lauren Groff

📚 Matrix, by Lauren Groff

Peter Yoon

How an epic and violent family history fuels fiction

“Part of why I write is to imagine this line, this thread, not only the history but, quite literally, family. I think no matter who or what I am writing about, I am creating a family for myself. I don’t know if that comes out as selfish. Like Maksim, there are relatives I have never met, and never will; there are aunts and cousins I met once and never will again; there are no doubt relatives who exist somewhere who don’t know I exist.”

📚 “Person of Korea,” by Paul Yoon

Adam Maida / The Atlantic; Getty

A fascinating portrait of a country at a turning point

“During this period, Zambra wrote primarily about the past, wrestling with the dictatorship’s ongoing legacy. The newly translated Chilean Poet, however, is the first novel in which Zambra looks primarily to the future, implicitly asking a new question: How does a society move forward after trauma, or—to put it as Zambra might—how does a country grow up?”

📚 Chilean Poet, by Alejandro Zambra

Felipe Estay Miller

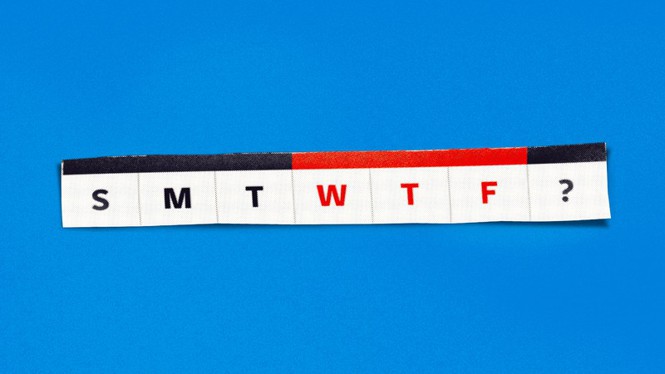

We live by a unit of time that doesn’t make sense

“It’s hard for me to prove as a historian, but I do think that when we are more attuned to this cycle, because it’s shorter than a month, it feels like time moves much more quickly. When our Mondays are different from our Tuesdays and our Wednesdays, it does kind of feel like, all of a sudden, It’s Monday again?! You can see in 19th-century diary entries that, more and more often, people describe this feeling by referring to how another week has come and gone.”

📚 The Week: A History of the Unnatural Rhythms That Made Us Who We Are, by David Henkin

Ken Harding / BIPs / Getty

The best time-management advice is depressing but liberating

“We are finite, limited creatures living in a world of constraints and stubborn reality. Once you’re no longer kidding yourself that one day you’re going to become capable of doing everything that’s thrown at you, you get to make better decisions about which things you are going to focus on and which you’re going to neglect.”

📚 Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, by Oliver Burkeman

About us: This week’s newsletter is written by Emma Sarappo. The book she’s reading next is Endless Endless: A Lo-Fi History of the Elephant 6 Mystery, by Adam Clair.

Comments, questions, typos? Reply to this email to reach the Books Briefing team.

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.