When Russia invaded Ukraine, the writer and photographer Yevgenia Belorusets began to journal about her experience living in Kyiv. The resulting account, which she published online in real time, provides insight into the conflict that more straightforward news coverage has failed to capture. It is, as she put it in an interview with my colleague Gal Beckerman, “a very complex picture of reality at a moment when war has turned everything incredibly awful.”

Belorusets’s urge to document and reflect when catastrophe strikes is not unique. Anne Frank’s diary of her time in hiding during the Holocaust is perhaps the most famous example. More recently, the early days of COVID spurred multiple public and private journaling projects, as individuals grappled with the awareness that they were living through history. Some hoped to supplement the eventual archive, while others simply desired an outlet for their anxiety. Regardless of intent, the resulting works are strange, quotidian reports shot through with deep fears about the surrounding tragedies. Reading the Dear America series, which features fictionalized diaries from young girls living through significant moments in American history, the value of this type of writing becomes clear: It models how to live in moments when global anxieties butt up against mundane concerns.

After 800,000 words and 25 years of regular journal entries, Sarah Manguso became an expert in this type of writing. Rather than limit her reflections to critical moments in history, she’s written continuously, sometimes dangerously obsessed by a need to create a record of her life for the times when her memory failed her. Though at moments this compulsiveness turned the impulse into a vice, overall the practice was, as she told my colleague Julie Beck in 2015, “the most useful tool I had in just trying to live thoughtfully, carefully, and responsibly.”

Every Friday in the Books Briefing, we thread together Atlantic stories on books that share similar ideas. Know other book lovers who might like this guide? Forward them this email.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What We’re Reading

Yevgenia Belorusets

Her world began to collapse, so she started keeping a diary

“There might be some sense of responsibility among people who are working with ideas to preserve a very complex picture of reality at a moment when war has turned everything incredibly awful.”

📚 Lucky Breaks, by Yevgenia Belorusets

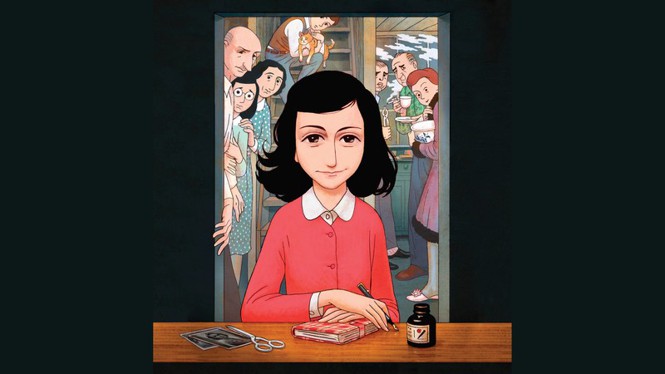

David Polonsky / Pantheon / The Atlantic

The quandary of illustrating Anne Frank

“Frank’s diary became one of the most famous narratives of the Holocaust, and because it’s written from the perspective of a normal adolescent living under the most abnormal circumstances, it humanized war and genocide.”

📚 Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation, by David Polonsky and Ari Folman

Millennium Images / Gallery Stock

Dear diary: This is my life in quarantine

“For now, writing these diaries is a comfort to their authors. Future generations may use them to understand what daily life was like during the pandemic—what Americans’ mask-wearing habits were, how much (and how safely) people socialized, or how they entertained themselves at home. These journals will provide history with the intimate details that make it come alive, and show us that even the most world-shattering events are made up of precious, individual lives.”

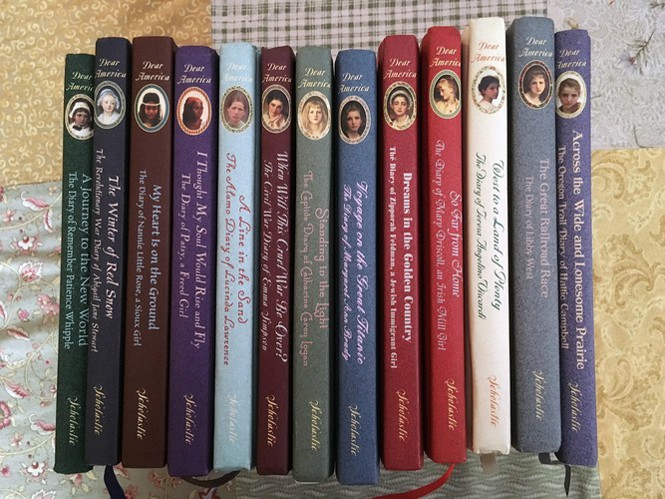

Scholastic / Amazon

Dear America: Reading through history

“Dear America didn’t spark my interest in history or even form the basis of my third-grade historical knowledge; but it showed me, forcefully, what history could be. It happens quickly, unplanned for. You can go to school on a Tuesday morning with the usual back-to-school butterflies and go to bed that night with a litany of new vocabulary words: terrorist, hijacking, rubble. The landscape of your childhood can change in a few minutes, and with it the significance of everyday acts. Very often, it takes a while to make sense, even to adults.”

📚 A Picture of Freedom: The Diary of Clotee, a Slave Girl, Belmont Plantation, Virginia, 1859, by Patricia C. McKissack

📚 Dreams of the Golden Country: The Diary of Zipporah Feldman, a Jewish Immigrant Girl, New York City, 1903, by Kathryn Lasky

📚 My Secret War: The World War II Diary of Madeline Beck, Long Island, New York 1941, by Mary Pope Osborne

Brad Greenlee / Flickr / The Atlantic

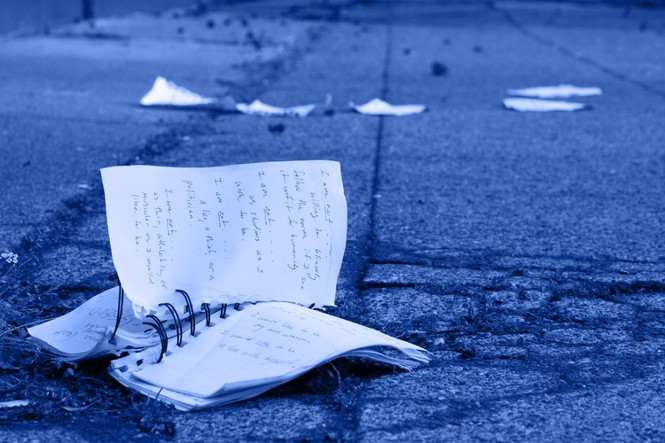

When diary-keeping gets in the way of living

“It brought me great solace to write things down and to make sense of them. … Every exchange that I had with another person, everything that I observed, every little throwaway moment I had on the subway observing this and that, the denseness of experience just seemed unmanageable without writing it down. After I wrote it down, it was a great relief to just have at least made that much sense of it in translating it into prose. So I guess it was a low-level constant anxiety attended by a simultaneous gentle relief. But it was a long time before that anxiety dissipated almost entirely, which is where I am now.”

📚 Ongoingness: The End of a Diary, by Sarah Manguso

About us: This week’s newsletter is written by Kate Cray. The book she’s reading next is The Copenhagen Trilogy, by Tove Ditlevsen.

Comments, questions, typos? Reply to this email to reach the Books Briefing team.

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.