Janet Malcolm once wrote that psychoanalysis requires the analyst and the patient to wrestle with an arrangement whose “radical unlikeness to any other human relationship” is dizzying for both parties involved. They consent to meet alone at the same time and place every week. Their mostly one-sided and confidential conversation is often staged with painstakingly positioned props: the couch, where the patient lies and lets their thoughts wander; the analyst’s notepad, where those thoughts are apprehended and transcribed, all in the service of hearing the patient’s underlying, unconscious needs.

That this therapeutic relationship—so awesomely abnormal, as Malcolm put it—has become relatively common speaks to how deeply Sigmund Freud’s ideas about analyzing the psyche saturate our world. A century and change since pairs began to meet in “sessions,” therapy is now a cultural trope. In fiction, for example, a premise that doesn’t seem to promise much narrative possibility—two people talking with each other in the same room again and again—becomes engrossing and mysterious. They vow, with a constancy unmatched by other commitments in their lives, to follow a largely unspoken contract of strict mores, and, as if casting a spell, invoke language as a cure.

More and more of us have been seeking entry into this arcane ritual. Last December, The New York Times found that nine out of 10 of more than a thousand American therapists reported that “patient demand” was growing. The realities of a pandemic, combined with the possibility of technology, have upended therapy: Many of us in treatment have reimagined the practice through our screens, sitting on our own couches. Chatbots can now offer a simulacrum of a fully objective, floating ear, incapable of judgment. Critics of these services have called attention to their glaring practical concerns: They can collect personal data, glitch, or just not be helpful. But these services also lack the grist of that risky, human relationship. There’s both threat and promise in the therapeutic encounter: the ineffable, fallible, and intimate play between two strangers, one witnessed and one witnessing, talking it out.

The books below—memoir, journalism, and scholarship—attempt to pin down what, exactly, occurs between two people in treatment. These texts are indispensable documents of human psychology for anyone who is willing to listen.

Psychoanalysis: The Impossible Profession, by Janet Malcolm

Malcolm remains the authority on psychoanalysis among laypeople who have written on the subject. This reported treatise on the inner sanctum of the New York psychoanalytic community in the 1970s, told through interviews with an anonymous practitioner, is a classic. It is also an excellent starting point for readers interested in a lucid summary of Freud’s thinking, and its evolution and application in America, with all of the internal splintering the profession is known for. Malcolm covers the conflicting views within the community on the relationship between analyst and patient. One view maintains that the relationship is solely bound up in transference—that the patient “transfers” their feelings, desires, and expectations originally directed toward one person, typically a parent, onto the analyst—and countertransference, in which the analyst does the same to the patient. In this view, patient and analyst are not really in a relationship with each other, but with each other’s misapprehensions and projections. Another view argues that there is a more real connection also at play, a “therapeutic alliance” that places the delusional dance of transference within “a placid relationship between two adults.” Malcolm lets the reader hear out both sides. Psychoanalysis: The Impossible Profession is the exacting work of a journalist and researcher, but it’s also a work of art, thanks to Malcolm’s position within the text. In a spellbinding reversal, it is she, the reporter, who plays the objective listener, while her subject, the analyst, bares their soul.

[Read: How Freud canonized himself]

The Last Asylum: A Memoir of Madness In Our Times, by Barbara Taylor

When Barbara Taylor first began psychoanalysis in the early 1980s, she felt “buzzed” about her status as analysand, or patient. A historian, Taylor began to experience flare-ups of anxiety when faced with a blank page; she would tear out her hair, so she began wearing a headscarf whenever she wrote. This book is a memoir of the turbulent psychoanalysis she underwent in an attempt to heal, and a history of the last gasps of England’s asylum system. Her thrill quickly corrodes into painful exchanges with her analyst: Their partnership can be marked, on her part, by a profound dependence, clouded with intense anger. Her addiction and self-destruction deepen until she commits herself to Friern Hospital; once a prominent psychiatric institution in England, by 1988 it stood partially empty and on the brink of closure. From inside, Taylor documents the state of mental-health treatment in England at a time of seismic change. She writes movingly of the life-sustaining relationships she made at Friern, with both fellow patients and psychiatrists, and mourns the larger loss of communities of mutual care that sprung up in these otherwise neglected institutions. Throughout it all, she continues her analysis, holding onto it “like a rock”: “To outsiders, the rites of psychoanalysis can look ridiculous,” she writes. “I came to see them as containers for the uncontainable, solid supports for emotional chaos.”

Citizen: An American Lyric, by Claudia Rankine

In a single page from her poetic exploration of the everyday violence faced by Black people, Rankine captures one of literature’s most revealing encounters between a narrator and their would-be therapist. The narrator, arriving at their appointment with a trauma specialist, finds the gate to the back office locked. When they ring the front door, the counselor barks at the assumed intruder. “You have an appointment?” she asks, the truth of the meeting dawning: “Then she pauses. Everything pauses.” As in the other microaggressions Rankine documents in Citizen, the power of this scene lies in the implicating and disarming second-person address, and the stark, unspoken racial dynamics at play. Rankine doesn’t need to tell the reader that the therapist is white, or that the narrator is not, to make clear that when she saw a Black person approaching, she did not see a potential patient. Psychotherapy, Rankine’s poem suggests, is yet another white backdrop against which people of color must stave off acts of dehumanizing misrecognitions. Yet Citizen can also allude to the necessity of a therapeutic relationship—a deep need to call out, to question, to return to, to remember, to speak of the past; and the twin need for someone to listen. Rankine writes, “You can’t put the past behind you. It’s buried in you; it’s turned your flesh into its own cupboard.”

[Read: Therapy voyeurism really might be doing some good]

Tribute to Freud, by Hilda Doolittle (H.D.)

Hilda Doolittle, writing as H.D., is a pillar of modernist poetry. After Victorian norms crumbled in the face of massive technological change and a traumatic war, her poems, novels, and essays attempted to create a new language to describe modernity. She saw Freud, and his writings, as an essential blueprint, and sought him, as a teacher and a doctor, in Vienna. She was reeling from the First World War, which led to the death of one of her brothers, and, in her mind, a stillbirth, the end of her marriage, and childhood baggage. She was also, although she dared not admit it to Freud, anxious about the rise of another war, one she correctly foresaw. Tribute to Freud contains two parts: Writing on the Wall, a memoir composed 10 years after her analysis and dedicated to her “blameless physician,” and Advent, her journal from that time. H.D.’s texts are personal testaments and also revealing documents of psychoanalysis in the first decades of the 20th century. They’re also tender portraits of Freud, who, like the practice he engendered, has become ossified by the weight of historical consequence. H.D.’s “idealization” of Freud, as Adam Phillips writes in his introduction to the text, “may be one of the preconditions for collaboration (as it is for parenting, and for falling in love, and indeed for reading and writing) … It could be the aim of a psychoanalysis to enable the patient and the analyst … to be free to be so interested and interesting to each other.”

The Examined Life, by Stephen Grosz

This work by the London-based psychoanalyst is an exemplar of a subgenre of memoir—recollections from a professional who, through hours of absorption in the psyche of others, becomes covered with the residue of existence. Grosz refines his records of treatment into tightly woven, sparely written vignettes that linger in readers’ minds. He was careful to ask patients, when possible, for consent to write of their experiences, and then to somewhat alter them to maintain the privacy at the core of the encounter. (After the book became an unexpected best seller in the U.K., Grosz noted in an interview, some patients could have been made uneasy by the fact that he hadn’t written about them.) One of the charms of The Examined Life is how it offers a portrait of a man who wears the struggle of sitting with enigmatic and troubling people. Writing about what he has witnessed offers a way for him to “work out something still from the case that is persisting” in him, like a toothache or an aftertaste. “I think that’s a surprise sometimes to patients,” Grosz said in the interview, “that they live in their analyst or therapist, that that goes on for a long time, sometimes years.” He hopes his case histories can challenge some of the more airbrushed depictions of analysis in popular culture, he continued, letting readers who might never lie on the couch “know what the real thing was like.”

[Read: The self-help that no one needs right now]

Playing and Reality, by D. W. Winnicott

This collection of essays by the cherished mid-century pediatrician and analyst explores several now-well-known psychoanalytic concepts: the transitional object, which aids a child through their detachment from the mother; the good-enough mother, whose infallible devotion gives way to instructive moments of slight frustration for her child; and the development of creativity as key to active and embodied participation in life. Winnicott also offers an illuminating examination of therapy as a form of play. To Winnicott, play allows for a fruitful “potential space” where a child’s inner fantasies become projected onto real environments, in a dance of imaginative symbolization that leads to personal growth. The possibilities of those activities persist in adulthood: “Psychotherapy,” Winnicott writes, “has to do with two people playing together.” In fact, the work that occurs is about enacting this potential. “Where playing is not possible then the work done by the therapist is directed towards bringing the patient from a state of not being able to play into a state of being able to play,” he writes. Though this is one of the denser texts on this list, and will require some patience and interest in the academic formalities of psychoanalytic theory, the perceptiveness and humility of Winnicott’s observations are worth the read.

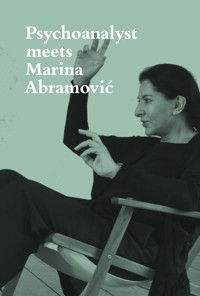

Psychoanalyst Meets Marina Abramović: Jeannette Fischer Meets Artist, by Marina Abramović and Jeannette Fischer

Marina Abramović is celebrated for performances that enact the extreme: risking pain, testing limits. In 2015, she invited the psychoanalyst and curator Jeannette Fischer to her house in the Hudson Valley. They set up microphones and recorded four days of conversation. Their conversation meandered among an analytic session, an interview, and an exchange between friends. Selected excerpts from their conversations are interspersed with Fischer’s analytic interpretations; the reader can see some of Abramović’s most memorable performances through the prism of her relationships with her parents and former lovers. Abramović’s art lends itself, almost agonizingly, to Freudian readings; her parents’ emotional abuse led Abramović to self-effacing performance that borders on self-negation, seeking a sense of control. In her celebrated work The Artist Is Present, Abramović sat motionless across from strangers, “staring into their eyes and focusing her entire attention on them,” Fischer writes. In other words, she offered a blank mirror to receive and reflect strangers who paid the price of admission to sit with her and be witnessed. Fischer doesn’t examine this interpretation, but she is the close listener, weaving Abramović’s telling of her life and art into meaning they can both make sense of. This double portrait of analyst and analysand shows the creative potential of this duo at its fullest.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.